Killer Context

Closing the loop on spec-driven development

TL;DR: I theorize that coding agent errors compound over time leading to increasingly worse outcomes as a session continues. I built Blackbird based on this theory, which restarts each task in a plan with a fresh context window, with a new task’s instructions as its starting point. This minimizes deviation from intention leading to better outcomes.

Note

This post (like all of my posts) was written by a human.

The rise of spec-driven development

In my circles, spec driven development is all the rage. It seems that tools like OpenSpec and spec-kit are brought up in nearly every other conversation. I am largely on board. If building with coding agents, I think that clearly defining what you want up front is absolutely necessary. My main issue with it, however, is that most spec driven tools stop short. They define the spec, but they offload the execution of that spec to an agent like Claude Code or Codex.

You might (reasonably) be thinking, “If you don’t want to have an agent build from the spec, then what would you have instead?” Well, of course in the context of agentic spec driven development the agent will be the one implementing the spec. My main qualm comes down to how these tools make that happen. Take for example OpenSpec’s /opsx:apply command. Its default behavior is to run through the list of tasks one by one, marking them done as it goes. At first glance this is great! You can spend your time on the high leverage work of defining the spec and offload the scut work of actually implementing that to the agent. Open your agent, /opsx:apply, done. But, in my experience, this is where things start to go wrong.

Compound interest

As Einstein once said (or didn’t say…), “Compound interest is the most important invention in all of human history.” Read any financial book or forum and you’ll inevitably hear about “getting your money working for you” by taking advantage of compound interest. And it’s true, it is a powerful concept that, if on your side, can lead to great benefit. But you need to be careful that it’s not actually working against you.

This brings us back to /opsx:apply. When you run that and let your agent execute your spec task by task, you need to assume some level of variance between developer intention and agentic output. What you get might be close to what you wanted, but it’s unlikely to be exactly what you wanted. With one task this variance can be reasonable. We can actually express this mathematically.

v = per-task retained accuracy (for “10% variance”, this is v=0.9)

pt = cumulative correctness after task t (normalized so perfect execution = 1.0)

p0 = 1.0 = perfect starting state

So after one task:

p1 = p0⋅v = 1.0⋅0.9 = 0.9

After the second task:

p2 = p1⋅v = 0.9⋅0.9 = 0.81

This is where we start to see what I call compound variance come into play. The formula generalizes for t tasks as:

pt+1 = pt⋅v

Let’s visualize this:

Cumulative accuracy (pt) by task count (click to expand)

| Tasks | pt (v=0.90, 10% variance) | Deviation | pt (v=0.97, 3% variance) | Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.00 | 0% | 1.00 | 0% |

| 1 | 0.90 | 10% | 0.97 | 3% |

| 2 | 0.81 | 19% | 0.94 | 6% |

| 3 | 0.73 | 27% | 0.91 | 9% |

| 4 | 0.66 | 34% | 0.89 | 11% |

| 5 | 0.59 | 41% | 0.86 | 14% |

| 10 | 0.35 | 65% | 0.74 | 26% |

| 15 | 0.21 | 79% | 0.63 | 37% |

After just 5 tasks with a compounding 10% variance, the outcome will have deviated from a perfect execution by over 40%. By the time you hit 10 tasks the outcome will have deviated from perfect by over 65%. You might be thinking that 10% variance per task is too high, but even if we reduce that to just 3% variance, after 10 tasks the deviation from perfect is ~26%. By the 15th task the deviation is ~37%.

Context as a liability

Recent releases from some of the largest AI providers have touted huge context windows as a benefit. The thinking goes that, ostensibly, a larger context window equals greater capability. But is that really the case? From the anecdotes of other and my own experiences, often when the context grows too large then the quality of a model’s output begins to decrease. This is acknowledged by the same AI providers who are releasing models with these massive context windows. This friction between feature availability and feature capability has led to the rise of context engineering – essentially designing systems that selectively manage what remains in an agent’s context window over time, removing the unnecessary information to keep the agent on track. It’s also why you see entire sections in agent documentation about managing context. But this process is imperfect, and Anthropic says it themselves right there:

As you work, context fills up. Claude compacts automatically, but instructions from early in the conversation can get lost.

And Cursor as well:

Long conversations can cause the agent to lose focus. After many turns and summarizations, the context accumulates noise and the agent can get distracted or switch to unrelated tasks. If you notice the effectiveness of the agent decreasing, it’s time to start a new conversation.

Who is to say that the compaction process won’t leave the agent lobotomized, with important information missing and irrelevant information retained, resulting in poisoned context? Bringing it back to spec-driven development, if your context window is compacted midway through your task list (or several times), how confident are you that the quality of the context that remains will lead to optimal outputs? Personally, I’m skeptical of this. In fact, I believe that compaction will ultimately contribute further to the decline in quality of responses. Consider the chart below:

Assuming a consistent compaction ratio of 20% (and I acknowledge that this is a simplification), repeated compactions steadily reduce the amount of free space available in the context window. As free space shrinks, compactions necessarily occur more frequently.

In a long-horizon, spec-driven execution, this is especially problematic. By the time execution of a task is underway, the active context already reflects an implementation that has begun to diverge from original developer intent. Compaction of this context does not revisit or correct that divergence, but instead preserves a compressed snapshot of it.

Subsequent compactions then add additional summaries derived from later stages of the implementation, each of which is itself based on earlier variance. Over time, the context becomes a stack of lossy summaries with no remaining access to the original intent. The result of this is not just information loss, but authority drift: the agent increasingly treats this accumulated history of approximations as ground truth.

To avoid this negative feedback cycle, my typical workflow has historically included starting a fresh agent session for each task, providing it only high level project information, the details on the new overarching goal of the feature, and the specific task information. I have found that it generally yields strong results. However, there are tradeoffs with this approach versus one long session, mainly:

- It’s slower because at the start of each session the agent has no context on your codebase and so must use its tools to search and hydrate it with relevant information

- It’s more token hungry because the above rehydration process has to happen for each new task

But, in addition to avoiding the building of a lossy contextual bedrock, it has other benefits too. Recall above the compounding variance chart. Another way to visualize that could be like so:

Deviation by task (1 − 0.9t, v=0.9)

| Task | Deviation (±) | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.00 | 100 |

| 1 | 0.10 | 90 |

| 2 | 0.19 | 81 |

| 3 | 0.27 | 73 |

| 4 | 0.34 | 66 |

| 5 | 0.41 | 59 |

This shows the exponential decay in accuracy as time, measured in tasks completed, goes on. But with a fresh session per task, we get:

In this image you see that variance resets to 0 at the start of each new task. This is because all of the context from the previous session is discarded and only relevant information about the task at hand is provided at startup. Essentially this treats agents as stateless. By doing this we avoid entirely the vicious cycle of repeated compactions.

Garbage in, garbage out

All of this is well and good, but it sits on top of one massive assumption: the plan is an accurate representation of the developer’s desired end state. In other words, it assumes that you’ve written a good spec and divided that spec up into accurate, detailed tasks that together describe the entire unit of work that you’re aiming to build. But what happens if you haven’t done that? Well, let’s recall our earlier equation for compound variance:

pt+1 = pt⋅v

If we change this up slightly to let q equal plan quality, where q is between 1-0, and let t continue to equal the number of tasks, we can see the impact of the plan quality with the following formula:

pt = q ⋅ vt

In other words, accuracy decays exponentially across tasks, while plan quality acts as a hard ceiling on the best possible outcome. That’s a pretty intuitive statement actually – write a bad plan, get a bad result. So how do we avoid this negative outcome? The answer is by ruthlessly editing the spec and task list, working to get q as close to 1 as possible. The problem is that it’s so easy to just accept a generated spec and a generated task list. In fact, OpenSpec even has a command for it: /opsx:ff. This is used in the very first example they show you when you go through their documentation, conditioning new users to accept their auto-generated artifacts. I would urge you to instead avoid these types of commands. Sure, use OpenSpec or similar tools to help in creating the initial spec and the subsequent task list, but make sure you’re reviewing everything closely and making required edits as you go so that you’re minimizing the variance from your intent at the very start.

Enter Blackbird

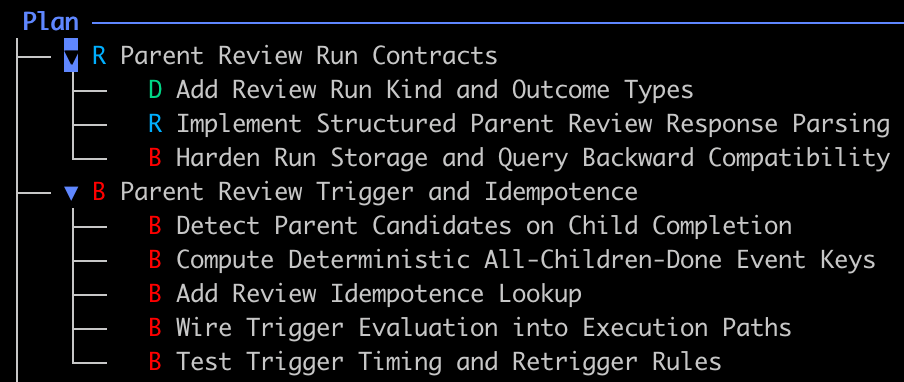

While this post is my first time formalizing these thoughts with words, I’ve had this intuition for some time. It has led me to begin building my own harness for spec-driven development: Blackbird. The core idea behind blackbird is to keep the agent “on track” as it works through a list of tasks generated from a spec. It does that by implementing exactly the flow outlined above: for each task in a given task list, a new non-interactive/headless session of your selected agent is started. A new session is given:

- A high level project overview

- Task specific information (goal, acceptance criteria, etc.)

- A default system prompt

Crucially we are not compacting the context from the session that implemented the previous task. If the agent determines that it needs any context on the work done in the previous session then it will use its default tools to search through the codebase and grab exactly what it needs. Blackbird will work through the generated (and hopefully reviewed!) plan one task at a time in dependency order, marking tasks done and unblocking downstream tasks as it goes.

As of writing, the blackbird codebase is over 15,000 SLoC of Go, excluding tests (and almost 30,000 with tests). Aside from the initial build in which I followed the general flow described in this post manually, blackbird was entirely bootstrapped, meaning every new feature added was constructed through a spec, a plan built off of that spec, and letting blackbird execute from that plan. Depending on who you are that will either turn you off from this project or serve as some level of validation of the pattern. Regardless, I’d love for you to give it a try and let me know your thoughts, good or bad.

Blackbird has some other features to push users towards measured, reviewed changes:

- Granularity control during plan creation, so that you can push the plan generator to create smaller, easier to specify changes

- The ability to review changes after each task is completed. You can accept, reject, or request changes

- Coming soon: the ability to have automated code reviews as chunks of the plan are completed

All of these are configurable, so if you did want to just let it rip you can do that too. Because each task has its own context window, blackbird can just keep chugging through tasks for as long as your token allotment allows.

Comedy of errors

It has been over three years since the initial public release of ChatGPT. There has been massive change in the field of software engineering, and there are no signs of that slowing down any time soon. Coding agents like Claude Code or OpenAI’s Codex are here, and they are good. But they’re not perfect, and the more you use them the more likely you are to recognize some issues:

- There’s almost always some variance between what the user intends for the agent to build, and what it actually builds

- If allowed, that variance will compound

- Eventually context windows fill, and the imperfect compaction processes employed by these agents cement any of that earlier variance as ground truth in the compacted subset of the context window

- As a context window compacts, its remaining free space is diminished, increasing the rate at which further compaction and degradation occur

When it comes to spec-driven development, these downsides are all at play. However, by taking a few pragmatic steps we can circumvent most of them:

- Ensure that your specs are detailed and accurate to your intention as the developer. Don’t let the AI have free reign over this process

- Ensure that any downstream artifact, such as a task list, is also closely inspected and edited as needed to match your intent

- Treat context as a liability, feeding the agent just what information it needs to do its job without confusing it or allowing the context of previous work to turn sour

I think by doing the above, you’ll find that you can take your spec-driven development to the next level.